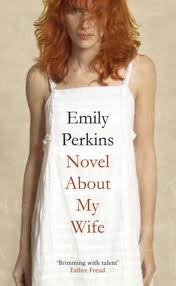

STATS: BOOK / EMILY PERKINS / 271 pp. / 2008

Truly and thoroughly about the jitters, in the full sense of that Dismemberment Plan song’s usage of that word. Things for the central couple here, trying to scrape by in their late thirties with a baby on the way, just get tighter and tighter and tighter, to the point where money, space, sanity, love, safety, geography, professional success, and upward mobility combine to form the flank of a giant boa constrictor which basically just keeps squeezing until the book has to end.

What’s touted as the central mystery — a guy’s formerly pregnant and now dead wife claims(ed) she’s (was) being stalked by a hooded figure … is he real or a figment? — ceases to matter all that much (though you still wonder, and sort of get to find out) as Perkins’ gentrifying, price-rising, cracked-out, knife-wielding teenager infested London of 2008 closes in and in and in and in around the two of them. Looking back on his wife’s death, Tom, the has-been scriptwriter who’s proxy-writing this novel about his wife, Ann, either to get to the heart of what happened or just to have something to write, finds himself trying to suss out who she really was, and whether he really knew her at all — even whether he ought to have been as afraid of her as she was, or claimed to be, of “the man” stalking her. In essence, whether, in her case, with regard to whatever she was so afraid of, it took one to know one:

“Really there are few conversations that are easy to remember, and even fewer actual statements. When I put words into Ann’s mouth, on these pages, it’s made up, of course, another way to get her to speak again. The way she talked, I can be faithful to that, and the occasional line. But mostly Ann and I, like everybody else, just asked each other to please pass the salt, and what we really meant was ‘please pass the salt.'”

Jogging in a dusky park, Tom gets locked in, and sees one of the gangs of 12-year-olds who haunt a lot of places in this book on the other side of the fence. He finds himself:

“standing there, waiting, my insides boiling as the boys levered themselves over the spikes at the top of the gates: the leader looked as though he’d done it a hundred times and knew just how to place his hands, like a Russian gymnast, supporting himself on his wrists to hoist himself over the top. The efficiency of movement made it clear there was no point trying to run. We could have been different species then, those boys and I.”

Teenagers seem often to be the most dangerous demographic, here and in life. Soon thereafter, increasingly aware of perdition’s imminence, Tom reflects:

“God, I have known what it is to stand on the cliff top looking down at the Whirlpool of Self-Pity. My toes have gripped the crumbling earth, loneliness bending me at the waist, arms windmilling to stay upright, stay on the edge, just watch that loose stone tumble down into the sucking water, see how quick it disappears from view. Self-pity must be resisted, not out of moral fortitude but as a means to survive.”

It just goes down and down and downhill as the baby gets nearer and then gets born (there’s a terrifically panicky scene in a deluxe baby-stuff store, as Tom and Ann get to the checkout aisle and realize all the baby-stuff they want is way out of their price range, but credit-card-buy it all anyway), and we keep flashing back to something weird and it seems somehow (maybe unspeakably) awful that happened in Fiji in the recent past, involving Tom, Ann, and the loutish (and maybe worse) film producer who fired him and basically killed his career.

The whole thing, by a still pretty young New Zealand author, is damn scary, and romantic, and sad, and totally engrossing in both a gaspy, air-sapped room sort of way, and in a chatty, sleek, modern, urban Euro sort of way, all wine and prosciutto, olive oil and shared bottles of wine … until it’s not. And there’s a kid in it named Titus Groan.

Whether you want to read the book as a grand “sorry state of the West at the end of the 2000’s” statement or not, there’s no escaping the cold devilish grip that Perkins’ portrait of white-people economic and marital woes manages to get on you. It pretty much makes you not want to try to live in any given place.

“The neighborhood was in the room with me, littered asphalt, chewing gum splodges, infested puddles.”